CLEVELAND -- There is a burly, angry man with a Chief Wahoo tattoo on the inside of his left forearm, and he knows I work for ESPN. That makes me the devil. We are standing inside the Cleveland Cavaliers locker room not long after their first game without LeBron James. The guy's name is Scott Raab, and besides being a native Clevelander, he's also one of America's best writers. His current project? A book that is part recount of James' breakup with the town and part meditation on the misery that comes with loving this place and its teams. Except he doesn't call him James. He calls him The Whore of Akron. You obviously see what's coming next.

He accosts me for my company's role in "The Decision" -- I actually understand his anger, though I won't say that to his face -- and I tell him what he can do to himself. He likes this answer, which is as Cleveland as his rage at the four letters on my press pass. Raab motions me over to the side of the locker room and digs around in his backpack until he finds it, safe in a plastic bag: a ticket stub. It's from the 1964 NFL Championship Game -- the last title the city won. He passes it to me carefully. Section 7, Row Z, Seat 19. Carrying this stub doesn't make him strange. It makes him a Cleveland sports fan.

LeBron's return

This is where Raab begins sobbing, wiping his eyes with a red bandanna, embarrassed, trying to get himself under control so he can finish the story. He changes the subject, composes himself and, 15 or so minutes later, continues.

When his friend got to Chapman's grave, he found it covered in coins.

That is Cleveland.

Then the Indians lost in the bottom of the 11th.

That is Cleveland, too.

Detroit Avenue and West 58th Street

I'm here to see what Cleveland actually thinks about LeBron James and his departure. To hang around town the week before the first Cavs game in late-October, talking, eavesdropping, leaning into bars, eating heaping corned beef sandwiches at Slyman's. To be around Clevelanders … then come out with a story.

AP Photo/The Plain Dealer/Marvin Fong

Tyler Gast, 8, and his brother Carter, 6, right, of Brook Park, Ohio, express their feelings about LeBron James leaving.

My first night in town, Michael DeAloia picks me up at my hotel. He's the former tech czar of Cleveland, someone who knows the importance of finding modern jobs to replace the vanished manufacturing. We head to a bar on the West Side, an old working-class place that's been reinvented. It used to be and now it is. They serve gourmet hot dogs, with dozens of toppings, from Oaxacan red chile and chocolate mole to vodka sauerkraut. We pull up a stool. We order a shot and a beer. The Wild Turkey burns. The High Life cools. Champagne of beers. Says so right on the bottle.

DeAloia settles in.

"There are literally parts of Cleveland that look like Rome," he says.

There are signs of death: closing mills, blocks of boarded-up buildings. There are signs of life: a thriving arts scene, a booming health care industry. On my first night in Cleveland, DeAloia tells me about both, one minute upbeat, the next realistic, describing a 21st-century success story and a 20th-century relic.

"It could be both," he says. "It's at a precipice."

Euclid Avenue and East 40th Street

Cleveland used to be. That's what Clevelanders will tell you, driving around the city, pointing at the remnants of a once great metropolis. It's like visiting a museum. Look, kids, this used to be America. This empty building used to be the Croatian newspaper. This empty lot used to be where John Rockefeller lived. This stadium used to be a stadium. This buried dust used to be Eliot Ness. Cleveland was home to the first home mail delivery, the first street light, the first streetcar, the first gas-powered car, the first X-ray, the first traffic light, and on and on. Life Savers were created here. So was Superman.Yes, Cleveland used to be the center of America's rise. This used to be a factory, and these used to be jobs, and this mill used to be a future, not a silent metaphor for the past. This city used to be home to the third-largest number of Fortune 500 companies. It used to be the home of 400,000 more people. Generations of talent have left, never to return. That's what they will tell you, and you will realize that there are two Clevelands: the one that exists today and the ghost city floating just above it, in the memory of the people who've been here for a long time, and in the imagination of those who just arrived. Everything is defined by these two competing narratives. My friend, Dave Molina, who is from Cleveland, told me this: "They're both myths. The only thing that isn't a myth is the present. But it's so complicated. It's much easier to be positioned at the intersection of two impossible myths."

LeBron was part of both myths, and, even in departure, he remains so; a reminder of what could have been and what once was.

He is a 6-foot-8 steel mill.

Euclid Avenue and East 93rd Street

And yet, Cleveland is.It is one of the world's three greatest symphony orchestras. It is dozens of ethnic enclaves, where people value their culture. It is creative restaurants, and elaborate gardens, and the best hospital in the world, which gets bigger and more outstanding every year. There are urban farms making use of blight, and a vineyard on the site of the Hough riots, and a booming biotech research industry. The city hired a well-known consultant who specializes in helping institutions reinvent themselves; his past clients include Wal-Mart and the United States Navy.

AP Photo/Tony Dejak

The city landscape continues to evolve. Plans have been proposed for a casino in downtown Cleveland, possibly on land overlooking the Cuyahoga River behind Tower City, left.

It is a complicated city with a common ethos.

"Everybody is gonna talk in a different language," DeAloia tells me that first night, "but there will be a unifying theme. It's what the Romans call a priori. A natural law. A natural truth."

So what is the natural truth about LeBron James? About his seven years here and his departure?

People obviously care about both. They care a great deal. Even the Clevelanders who insist they don't care prove themselves wrong with their fervor. Here's an example. One passionate, pink-haired citizen leaned across the table and said, her voice rising, "LeBron is not Jesus. No one gives a f--- what he's doing. LeBron is not my messiah. LeBron James did not personally piss that lake."

There are strong emotions. But why?

Why are people here so outraged that a basketball player left town?

East 9th Street and Marginal Road

It starts with love.Cleveland is a town that loves. It loves its own history, and the harsh winters, and parish bake sales, but, mostly, it loves to root. Clevelanders root for new stadiums and old teams, for shiny halls of fame, for jobs and urban gardens, for gritty, blue-collar athletes.

AP Photo/Mark Duncan

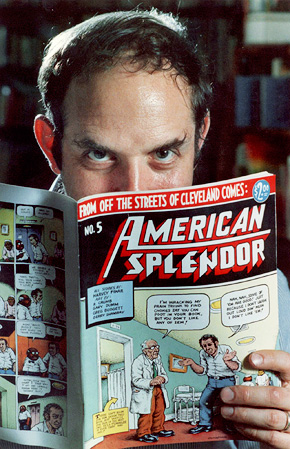

Harvey Pekar, a famous comic book author, was critical of Cleveland fans' unquenchable thirst to cheer for something, or someone, in their city.

That's what Cleveland's greatest poet thought. His name was Harvey Pekar, and though he wrote famous comic books, he never left his day job as a file clerk at the V.A. Hospital. His stories told not of faraway adventures but of the everyday struggles of a man living in the black-and-white streets of Cleveland. He made the ordinary heroic.

One of Pekar's stories is titled, "Why I Haven't Visited the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame." The Rock Hall, as it's called here, was one of four wildly expensive public projects built in the 1990s. The Indians and Cavaliers got new homes, then the Browns left (you could write volumes about the trauma of that), then the replacement Browns got their own new stadium, too.

The town and its residents bet on sports. They bet, hoping that by building big they could again be big. They bet, scared that losing their teams might prove them small. They built, then they pulled for those projects to be successful. Pekar railed against his fellow citizens' unquenchable need to root. He writes:

Reason No. 1 is because it's supposed to exemplify Cleveland, the comeback city, the city that bounced back from the Cuyahoga River catching on fire. But Cleveland's not a comeback city. So what if there are more clubs around downtown. That's papering over the problems. Unemployment here is relatively high. There's a lot of poverty, which leads to poor school performance and more poverty. I would hope the performance of Cleveland school kids, which was the worst in Ohio, would mean more to local residents than a rock n roll show in a football stadium. But it doesn't. The connection between boosterism and the Rock Hall is nauseating.

This was published in 2000. Three years later, LeBron James was drafted by the Cleveland Cavaliers. Unprecedented boosterism ensued. Seven years later, he went on live television to break up with the city.

Four days after "The Decision," Pekar died.

West St. Clair Avenue and West 6th Street

Courtesy Thomas Mulready

Thomas Mulready runs CoolCleveland.com.

Who will Cleveland miss more?

That question is a proxy for a larger, more difficult one:

Is the future of Cleveland in the image of LeBron James or Harvey Pekar?

Cedar Road and Delaware Drive

The answer is in a jazz club, named for a Joycean allusion, with low light and peaty scotch. The band is sound-checked. The Mose Allison poster is on the wall. Charles Michener, who wrote for The New Yorker, comes into Nighttown and orders a Hendrick's martini. He's writing a book about Cleveland, too -- he grew up here and recently moved back -- and it's about the constant search for reinvention."Rebirth is the story," he says.

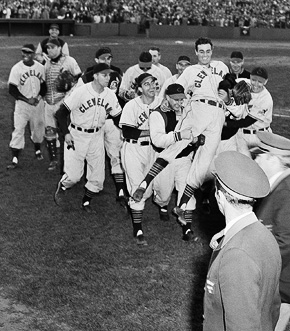

AP Photo

Cleveland Indians teammates carry pitcher Gene Bearden off the field at the end of an AL pennant playoff game against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park on Oct. 4, 1948. Cleveland won 8-3 and went on to face the Braves in the first game of the 1948 World Series.

"Here's one of my favorite things in Cleveland," he says. "Signed 1948 Indians World Series team. I was there. I was 8 years old. Look at these guys. I weep when I look at this picture."

There's Bob Feller, and Lou Boudreau, and Larry Doby. That was a good time in Cleveland. The city was still growing, with more than 40 percent of the jobs in manufacturing. Then, just two years later, it hit the ceiling.

The population of Cleveland peaked in 1950.

The decline began. The '54 Indians lost the World Series. Forty-one years passed before the Indians reached another. The decline grew steeper. Fortune 500 companies left town. Factories closed. The Steel Belt became the Rust Belt; today, only 13 percent of jobs are in manufacturing. Things kept going down until 1978 -- the low point -- when the city defaulted on its loans. Cleveland was busted.

The theme of the city since 1978 has been reinvention. There's a constant search for a new reason to be, which is what Michener is writing about. In the 1990s, the reinvention was based on the three new stadiums and the Rock Hall revitalizing downtown. The Flats were developed as a magnet for entertainment dollars. The mayor during all of this was Mike White, and after he left office, his former best friend, Nate Gray, went to prison for corruption. The FBI looked in to White, but he was never charged with a crime. Everyone in town has heard the whispers. "This is a town where graft is spelled with capital letters," DeAloia says.

AP Photo

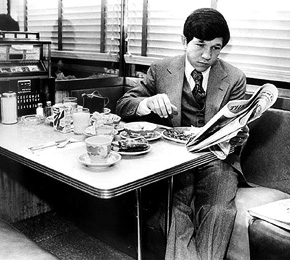

Cleveland once had another hero -- Browns running back Jim Brown.

A year later, LeBron James arrived.

"LeBron James is a great symbol for what's right and wrong," Michener says. "Cleveland for too many years has lived in a kind of unreality about the benefit of being a big, major league sports town."

Michener knows the siren call. He loves the 1948 Indians and felt the same way about LeBron. "I was caught up in it," he says. "I felt LeBron James was very important. We all went too far. Cleveland, in its desperation, went too far."

Now LeBron is gone. Has this taught them anything? Did the flames of The Decision burn hot enough to make Cleveland let go of its rooting obsession?

"I think Cleveland learned a lesson," Michener says. "I hope so."

They have to figure out what's next. Their problems actually have little to do with LeBron James, so maybe he was a distraction from solving them. They don't need sizzle. They need steak. The current mayor, for instance, is both popular and boring. Michener calls him the "invisible mayor." The new heroic is reliable and competent. Glitz, after a seven-year fling, is out.

Harvey Pekar would be proud.

Garfield Boulevard and East 86th Street

Garfield Heights, Ohio

If hope lives in the back tables at Nighttown, reality lives near the jukebox at the Venture Inn. I've come for a cold beer and a shot of reality. I get many rounds of both.

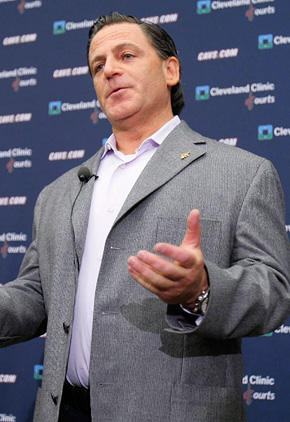

AP Photo/Tony Dejak

Cavs owner Dan Gilbert told fans in an open letter how the departure of "our former hero" was "bitterly disappointing to all of us."

It's Friday afternoon. The music is classic rock. The televisions are showing Browns news. The owner of the bar works in the mill. Most of the customers do, too. The union bosses set up shop along the back wall, introducing me around, talking to their guys.

"This economy is kicking our ass," says union official Pat Gallagher.

His co-worker, Sherman Crowder, tells me his story. He was born in Cleveland, the son of a guy who migrated from West Virginia in '54 searching for jobs, and he went to the mill right out of high school. Two factory offers in two weeks.

"You can't get two jobs in 10 years nowadays," he says.

"Pat came out of the mill, too," he says. "He and I came out of the same mill. He went to college for a little while."

"I was almost 20," Gallagher says.

Crowder lives just a few miles from LeBron's house. One of the guys hanging out back here installed the acoustical tile in LeBron's home theater. I ask a dozen or more people what they think, and all of them say: It's not that he left for greener pastures; it was how they thought he showed them up. They think he rubbed their noses in it.

"I was all right with him leaving," Crowder says. "I didn't like the way he did it."

Everybody says that. I've heard it from the owner of a steakhouse, The Lancer, that's a gathering place for the African-American community. I've heard it from a homeless guy who cleans the Cavs' arena. I've heard it from a right wing radio host and hipster liberals and architects and ex-cops and a James Beard Foundation Award-winning chef. If you talk to regular people who pulled for LeBron, you'll hear a nuanced opinion that doesn't jibe with the hysteria we saw from afar. To a man, that's what these guys at the Venture Inn say. They aren't naive. They don't give Gilbert any passes. "He made money on LeBron," one guy calls out, "so he ain't no damn saint, either."

These dudes work hard for a living and don't ever begrudge someone doing what's best for himself. Life ain't easy in the world. It's hell near the furnaces. They wear long johns in the heat -- a few minutes inside, they soak with sweat, which cools them off. At closing time, guys head to the bar for a beer. "You order two," a steelworker cracks, "and you pour the first one on your head."

They feel lucky to have work. The jobs that still exist might not for much longer.

"This town is dying," a customer says. "If I could leave, too, I think I'd be out."

"Why?" the bar owner asks.

"The future's not bright in Cleveland," he says.

That's why they understand. Many of their sons are the first generation to not find work in the mines or the mills. Their own children, when faced with LeBron's decision, made the same one. So the men at the Venture Inn aren't angry. They get it. Tim Flor's son has a great job at a hotel in Orlando, Fla., makes a good living and often surprises his Pops with tickets to big Cleveland sporting events. They've been to see LeBron play together. Tim shows me his son's business card.

"I'm proud of my son," he says.

"The way he did it was f---ed up."

-- LENNY SOFRANKO, STEELWORKER

"The way he did it was f---ed up," says Lenny Sofranko, a steelworker for three decades.

These guys have a code.

They think LeBron broke it.

Mulberry Street and West Bagley Road, Berea, Ohio

That mill town spirit has outlived the belching smokestacks. It remains in many places, perhaps most of all in the way Cleveland fans love their teams -- and the way they expect those teams to play.Take Eric Barr. He's a Browns fan. He grew up in Connecticut, but his dad worked in a factory and loved the Browns, which made his son love them, too. The things the team represented meant more than geography. So Barr bought season tickets, and he drove 500 miles to every game until, a few months ago, he quit his job, left behind a steady check and benefits, and moved to Cleveland. He still hasn't found work. He lives out of a suitcase. He is lonely except for the few hours he communes with other fans on game day. He plays solitaire. He spends his days at a library looking for jobs. The money's gonna run out. Things seem bad. He wonders why he did this. He's 33, alone, with no furniture, no job, no future. But a few days ago, a glimmer of hope arrived. He got a call from a fellow Browns fan. Guy lived in Tennessee and read about Barr in the paper and wanted to do something. The Samaritan gathered oak and cut it into boards, smoothing each one, carefully putting them together, using his own hands to build someone he'd never met a bed. Then he delivered it to Barr. A man ought to have a bed. The Browns fan refused to take any money. All he wanted was a promise from Barr: When you're on your feet, do something kind for a stranger. That's what loving sports really means: giving part of yourself to someone you'll never know because the giving makes you feel good. At their worst, sports fans in a place like this can be crazier than the craziest ex-girlfriend. But at their best, they create a community.

They are willing to do something kind for a stranger.

Center Ridge Road and Walter Road, Westlake, Ohio

AP Photo/Amy Sancetta

"Do unto others as you would have them do unto you," says Cavaliers guard Daniel Gibson. "So whenever I get loyalty, I give it back."

The fans seemed to sense how much it mattered to him. They saw themselves in him and, soon, he saw his own past in them, too. Their blue-collar spirit reminded him of back home in Houston. Their love kept him going. He made the team. He's a fixture now. Not a star, but beloved.

"They cheer for guys who leave it all out there," he says. "They want to see their city represented in a way that they go about their day. They go about their days working hard and without taking anything from anybody."

Gibson is on Twitter, and he regularly talks to his fans. He sees it all: the love, the anger, the hate. Their messages are a window into Cleveland's obsession with its teams. He sees all the tweets that say, simply, Believeland. He understands.

"It's a passion," he says. "It's deeper than just sports and seeing us play the game. It goes into the city and the way they care about the representation of Cleveland. The way they put their hard hats on every day."

We're talking about how some players get it and others don't, how some players need it and others don't. I point to his Houston Astros medallion and ask why he still loves his hometown team. He's a pro athlete … and a fan.

"That's how my parents raised me," he says. "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. So whenever I get loyalty, I give it back."

Gibson hangs out at his local pub, watching the television, silently checking out LeBron's new commercial, talking with the bartenders and fans. It's not what he thought pro ball would be like. It's not L.A. He likes that. It reminds him of a simpler time. Sometimes, small is good.

"It definitely gives you that genuine feeling," he says, "like when you played on your high school team."

East 185th Street and Kewanee Avenue

That is Cleveland.Community matters, which is how I ended up with a glass of moonshine in front of me. I'm at the Lithuanian Club. The men at the bar are talking in Lithuanian, watching the Browns game on TV. They are tough old dudes, many of whom literally walked out of Lithuania after World War II with nothing to their names and no idea where they would go. They ended up here, searching for jobs, building a life.

Everything is Lithuanian. They want their daughters to marry Lithuanians; a young Irish lawyer at the bar tells me about courting his wife, and it sounds a bit like "My Big Fat Greek Wedding." The posters on the wall are in Lithuanian. There are displays for every Lithuanian athlete, from Unitas to Laurinaitis, with special care given to the two they know best: Joe Jurevicius, a local whose father is a regular here, and Zydrunas Ilgauskas, who left Cleveland to go play with LeBron in Miami. Ilgauskas visited a time or two, showed that he understood his roots, and they love him for it. He made the effort, so they begrudge him nothing. Fans don't need much in return for their love.

They pour me a shot of krupnikas. Every family has its own recipe, a carefully guarded mixture of spices, honey and pure grain alcohol. Then they ask if I'd like to come see something. We climb a staircase and go into a kitchen. Along the way, I'm told the story: a local man, Benny Butkus, had dropped dead several weeks before. He made a famous krupnikas, and that year, before he passed, he'd already bought his ingredients. So in this kitchen are his children and his wife, standing over a stove, cooking up his moonshine for the last time. Cleaning bottles, stirring pots, checking spices. They are doing it together, through their pain, a tribute to a man who loved his family and his city, who valued loyalty, hard work and pride.

"This is the widow," I'm told.

It's a beautiful moment, and, for the first time, I really began to understand this difficult city, and understand the things that matter here and the things that don't. They didn't love Ilgauskas only because he was a great player; they loved him because he appreciated where he came from. They loved LeBron James for the same reason. They thought he was part of them. They hung his picture in their club.

They never imagined he'd come to this place, or that they'd ever get to shake his hand. But they did believe -- because, like them, he was from northeast Ohio and grew up poor -- that he understood why making moonshine on a Sunday afternoon is important.

They thought he understood.

Everyone did.

Idlebrook Drive and Crystal Lake Road, Akron, Ohio

It's 28 miles from the arena to LeBron James' house.I'm hoping the drive will offer clues into this communication breakdown. I'm in the passenger seat. A local attorney and blogger, Peter Pattakos, is driving. We leave the industrial gray of the city and drop into the valley, alive with the oranges, reds and yellows of fall. This was LeBron's daily commute. The tires hum on the interstate as Cleveland gets smaller behind us.

"We're out of Cuyahoga County," he says.

AP Photo/Plain Dealer/Chuck Crow

James' house was built in the suburbs in 2007.

He also saw what fame did to LeBron. It didn't change him as much as it changed his world. It's inevitable, really. Walls formed, connections slipped away. By his senior year, something was different. "LeBron's not around anymore," Pattakos says. "And Maverick [Carter] doesn't return anybody's texts anymore. You see the bubble forming."

Soon, we're here. Exit 137B. We follow LeBron's postgame drive, taking a right at the Outback Steakhouse. The leaves are incredible. It's wooded. Peaceful. Pattakos turns on Idlebrook Drive. There it is. Sprawling, with a guard house. It's a beautiful home, modern. The place is decorated for Halloween with pumpkins and gourds. We drive past, and I notice that the house next door is a simple colonial. The entire neighborhood is middle to upper middle class. Nice homes, but nothing crazy. This isn't a house built to sell. Nobody will ever buy this house. "People have to learn to forgive LeBron," Pattakos says. "He'll be back. We've got to let him come back."

Strangely enough, I think of Graceland when I see the place. You go to Graceland expecting to make fun of it, but you end up feeling the struggle it took to have a house like that. The struggle sits on your chest. This seems the same. Sure, LeBron built a house that in no way fits with the other homes on the street. But that fades away when you look at it. LeBron rose above every possible obstacle. He made it, and this is the house he built when he did. There are much nicer neighborhoods off this exit, secluded lots tucked into the streams and the trees … and, in Cleveland, there are the old, lakefront estates of the industrial barons that rival anything in the Hudson Valley. True palaces, with entrances for staff and private marinas, relics of a bygone era of wealth and possibility. But that wasn't what LeBron created. His greatest dream, it seems, was to make a life in a perfectly normal, nice suburban subdivision. It's so clear now. LeBron James went from poverty to the bubble of celebrity. He's spent his entire life on one of these two islands. He's not from northeast Ohio.

He's from his own struggle.

College Avenue and Professor Avenue

Carlo Allegri/Getty Images

U.S. Rep. Dennis Kucinich says that the people of Cleveland felt a powerful connection with LeBron James and that when he left, "people were heartbroken."

Kucinich grew up rough -- he's written a heartbreakingly good memoir about it called "The Courage to Survive" -- and the sports teams anchored him. He sneaked into Municipal Stadium. He kept a 1948 Indians pennant above his bed, and at night, he'd walk the neighborhoods and listen to the radios play through screen windows. This never left him. In the 2004 presidential debates, he kept three photos on his lectern, to center himself. There was a photo of his mother, and of his daughter, and of Rocky Colavito.

Kucinich knows his city -- he was mayor at the low point in 1978 and has represented it in Congress since 1997 -- and he knew as LeBron was announcing his plans how much it would hurt. He listened to The Decision in his car, parked in his driveway. He couldn't go inside until it was done. When he turned his car off, he was heartbroken for his city. I ask him: Did LeBron not realize how people would react?

"We have to remember," he says, as we navigate Cleveland's streets, "he's still a very young man. The Scottish poet Burns once wrote: O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us, to see oursels as others see us. Even though I'm sure he's very aware of the status he has here, I don't think that he could have possibly imagined the close emotional connection people had with him."

Kucinich looks at the buildings, at the bent but not broken city out the window, rushing past in a blur. He says that LeBron is just 25. People often do things they later regret. Even Kucinich had a reputation when he was mayor as a rigid firebrand, and all the conflict he seemed to enjoy might have hurt the city instead of helping it. His willingness to take a stand is the same now as it was then, he says. But is the way he dealt with things?

"No," he says.

When he looks at me, his boyish face is creased with lines.

"The word character comes from the Greek word kharassein, which means markings. There are indelible markings we have, so aspects of character will be with us throughout our life, no matter what office we hold, no matter how good we may be in sports. There are some things we carry with us in life."

AP Photo/Cleveland Plain Dealer

Kucinich, who was mayor in 1977, is convinced that James will learn from all of this.

"Let me tell you," Kucinich says, "you walk into an old stadium at night, you can still see ghosts dancing. You can still see a ghost running out a ground ball or sliding into second or going to the fence to field a long fly ball. You can hear the crowd cheering. It's the same phenomena in the movie about Gen. Patton. When he went onto a field, he could sense the battles that happened. Our memories really have the capacity to re-create a moment."

So the sports teams here are beloved because they are among the few parts of the ghost city that also exist in the present?

"Even though I'm sure he's very aware of the status he has here, I don't think that he could have possibly imagined the close emotional connection people had with him."

-- U.S. REP. DENNIS KUCINICH

"That proves something that takes us from baseball into quantum physics," he says. "That is that the creation of segmented time created a false construct of past, present and future. In human experience, what we call the past, present and future exist simultaneously. So when you talk about sports memories, it's very real. It's a false distinction to say that was yesterday."

What's yesterday?

"Exactly. We live all of it now."

But people thought LeBron knew, I say. They thought he understood their past, present and future, and his place in all three. Clearly, he didn't.

"You're talking about a deep love that people had for him, as a player, and also coming from the area," Kucinich says. "There's a very powerful connection, and people were heartbroken."

Was that connection real or projected?

"I think that happens to anyone in a relationship," he says. "It's not just sports and politics. Any relationship can have that dimension, where people read more into it than is there."

So is all the parsing a smokescreen? The endless quibbles over whether it was the leaving, or the way he left, or how he didn't allow the Cavs time to chase free agents, or that he wore a Yankees hat, or that he quit in the playoffs, or that he broke his promises. Are people angry that he didn't care as much as they did? Are they hurt and struggling to express it?

"It was a relationship where one party to the relationship just left for somebody else," Kucinich says. "Those are painful moments. There is deep pain that comes from that. But the people in this town, there's a lot of heart here. People heal. And they even forgive. They don't forget, though."

AP Photo/Tony Dejak

James follows the big national teams like the New York Yankees and the Dallas Cowboys.

Detroit Avenue and Marlowe Avenue, Lakewood, Ohio

The markings conversation sticks with me. LeBron took seven years of cheers as a fee for services rendered. He made them his cheers. The fans were lucky to be witnesses. They deserved nothing in return for their love except great basketball and excitement. But it's not always that simple, and somewhere inside, James knew it. Not long ago, he talked about the Saints and the city of New Orleans: "Just look at what the Saints did for that city. All that city went through, and then to the Monday night game where they played the Falcons, and blocking the punt, and all the way to winning the Super Bowl, that's very emotional." What he understood in others, he either ignored or failed to understand in himself. Maybe he was too insulated. Maybe he was too young. Maybe the love of a city like Cleveland is too small a dream -- or, maybe, it's too big. Instead of grasping the golden ticket to Legend, he seemed to want the ordinary one to Star, the sporting equivalent of a perfectly normal, nice suburban subdivision.Whatever the reason, he didn't get that Cleveland felt about him the way New Orleans feels about the Saints. And, as he ends one chapter of his life and begins play in another, those are just some of the markings LeBron doesn't yet have.

J.D. Pooley/Getty Images

Police stood guard at the site of the giant Witness banner after James said he was leaving for Miami.

Ontario Street and High Street

The first game of the season begins in five hours.

AP Photo/Amy Sancetta

Workers removed the banner in July, two days after James' announcement.

That enormous billboard summed up so much of what went wrong. This wasn't L.A. or New York. This was Cleveland, city of ghosts and dreams. In a place trying to rise again, LeBron wanted to be portrayed, or allowed himself to be portrayed, as a savior. He would erase past pain with his own sacrifice. He was the King James version. He did a Jesus pose on a downtown building. They pulled for him with a corresponding religious frenzy. Now the spell is broken.

The arena is across the street. The sky is blue. A vicious wind roars in off the lake, ripping the page from my notebook. One driver honks and waves. A few others snap cell phone pics. Mostly, people stand before it in silence. Typically understated.

"That turned out nice," one says.

The banner is a picture of the skyline. It's an ad for Sherwin-Williams, a company founded here. The text reads: Our home since 1866. Our Pride Forever. This feels right. A madness has ended. LeBron James' Cleveland is gone. Harvey Pekar's Cleveland is back. A Christ-like photo of a player has been replaced with one of Cleveland itself.

East 4th Street and Prospect

People pour into Downtown. This is a celebration. The bars are full. Across the street from the arena, a wonderful Italian restaurant named Chinato is full, too, with people getting in a quick meal before tipoff. I'm meeting Michener for some pasta. I am suspicious of the excitement. Is this about the reinvented Cavaliers or is it a proud city's attempt to show LeBron it doesn't need him? Is it a hopeful nod to the future or a defiant fist to the past? LeBron's shadow still lingers. Sure, the season tickets sold out, but they were sold out before he left. What does the future hold for basketball here?"We don't need him," chef Zack Bruell says.

Business hasn't suffered, Michener says, pointing at the dining room.

A look of worry passes over Bruell's face. It surprises me.

"We'll see next year," he says.

Ontario Street and Huron Road East

The arena is ready.The Boston Celtics are in town. Last night, they beat LeBron James and the Heat. Everyone knows this, and the place feels electric. The team slogan is everywhere: All for one, one for all. New coach Byron Scott tells the crowd exactly the right thing in a short welcome.

"We want to thank you for your love and your support," he says. "One thing I promise is you're gonna get maximum effort. These guys are gonna play hard every night."

The crowd roars, and the game begins, and Cleveland hangs tough and the place is on fire. I even tear up a bit at the crackling energy. It feels like the first semifinal game at the Final Four. It's so damn earnest I can't stand it.

The game hits the fourth quarter and, with about five minutes left, the fans realize the Cavs have a shot to win. There's a timeout, and a series of montages is played. Then something happens. The video cuts to a shot of the new banner. The banner with the skyline of Cleveland.

The crowd goes insane, and the game ops guys just leave that image on the screen for the longest three or four seconds of the night. My God. They. Are. Going. To. Win. This is, for one night, a communal act of defiance against a nation's celebrity culture. This is for the steel workers leaving the mill, and for the crowds at The Lancer, for Harvey Pekar, who'll be buried near Eliot Ness, for the young plotting reinvention, for the middle-class Lithuanians, for everyone who ever loved something that didn't love them back. I look around me. Scott Raab is talking furiously into his tape recorder. The fans come to their feet, in Mark Price jerseys, in Austin Carr jerseys, in Delonte West jerseys.

Down the stretch, Boobie Gibson is incredible, hitting shot after shot, feeding off the energy of the fans who breathed life into his basketball dreams. He started off the game abysmal, 0-for-8, but when it counts, he's got his hard hat on. He makes his free throws in the final 17 seconds, and they've done it. A microphone appears in Gibson's hand, and he looks up at this arena gone nuts, this city gone euphoric, with cheers rolling down to the floor.

"We appreciate y'all," he says.

That is Cleveland.

The next morning's front page refuses to print the words "LeBron" or "James." The paper calls him "The Player Who Left."

That is Cleveland, too.

(ESPN)

No comments:

Post a Comment